“I have never met a person who is not interested in language.” (Steven Pinker)

Ghanaians habitually overlook secondary manifestations that are attached to primary purposes. Local language instruction may be cited as one such instance. Forcibly forging ahead in traffic where rather a concessionary stance would ultimately have been a prudent strategy for one-and-all is another.

The Government of Ghana’s policy attempts at local language instruction are all-too-often misunderstood, derided, or rejected outright by many of its citizens. The lynchpin of this conceit of many a citizen lies with their steadfast belief that “vernacular” instruction will ultimately be a gluttonous journey on a famished road towards an inconsequential destination; when rather it is a scenic route, linguistically speaking, towards a panoramic perch overlooking a lush lingual landscape.

Local language instruction is not totally about the teaching of local languages in schools. It is not even the primary purpose and it is also not the secondary manifestation that is being sought after; especially as it concerns “vernacular” proficiency. Academically, the primary purpose of local language instruction in education is about getting a pupil to gain a full ‘intelligence’ in language; whereas the secondary manifestation is ultimately about a pupil gaining a command of English, the nation’s and the world’s reigning official—though not only ‘proper’—language.

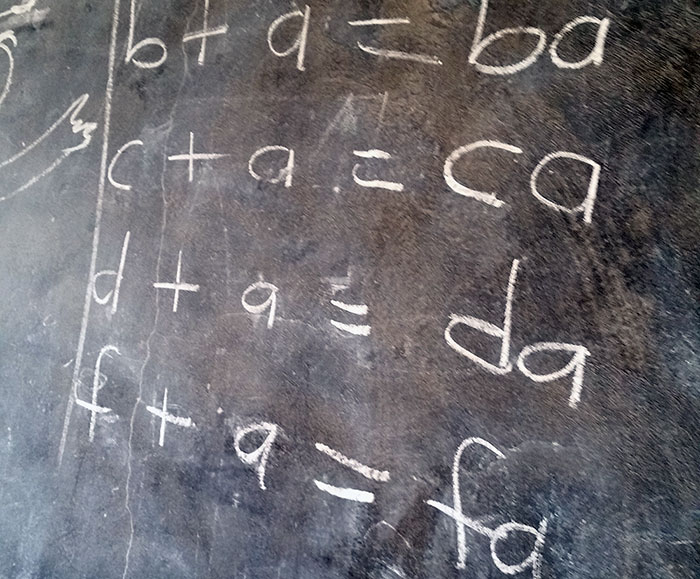

Altogether, the mastery of language, English or otherwise, comprises one of the overriding goals of local language instruction. The commonly-shared and consistent road signs and demarcations as well as the navigation signals and comportments of just about any language may be best understood and shared via the use of the language a child knows best when they attend school for the first time, going forward and well beyond as well. The common sense of local language instruction simply consists of teaching a child about language in their own language. This same sense extends to subjects and topics such as numeracy and reading as well as other discerning details like a child’s intellectual development as well as the beginnings of his/her socialization – for example nomenclature (i.e. the naming of universal and/or common items and concepts).

Many a citizen’s conceit centers on their belief that local language instruction—at once needlessly and primarily—teaches pupils about their “vernacular;” and secondarily, it rests on the attitude that this detour into vernacular retards the pace of their children’s mastery of almighty-English. Some parents and their fellow detractors appear to be asking the following question: “Why veer off course to indulge in the cultural artifact of “vernacular” where rather strident progress towards the commanding heights of utilitarian English is urgently needed; especially if it comes at the expense of their children’s academic as well as economic potential and promise?”

It is almost as if there is a passive-aggressive war of words between the issues of cultural relevance and academic impracticality, where rather there ought to be a truce between the ideas of policy realization and logical rigor. There really is genius to this perceived madness of teaching with the use of a local language in order that mastery of any-and-all languages may reign; and yes, globalized English most especially—if one so wills—may be attained and gainfully applied to pupils’ cultural, academic and/or socioeconomic realms.

The needed tautness and the dreaded tension between the permission inherent in the words “may be” and the resignation hidden in the word “maybe” is the lingual albatross around Ghanaians’ collective necks when it comes to the blossom and bloom of local language instruction and its intentions. Local language instruction may be the panacea for many a Ghanaian’s ill-facility with language[s] if properly implemented. To know that the successful navigation of language rests on the “may be” whereas the public citizens’ predisposition wrestles with “maybe (not)” is tantamount to one-and-all possessing a willful ignorance about the efficacy of indigenous languages as they may concern the constructs of learning.

This willful ignorance about the role of language in instruction and its use to articulate learning has been learned and unlearned respectively over the decades. Once before, Ghanaians learned in their local languages (also known as L1) before transitioning to English (a.k.a. L2), with some of them going on to learn Latin in order that the root and flowering of L2 was ultimately made of facility to and for them. Many of this type of Ghanaian went on to study medicine in Germany, Agriculture in Czechoslovakia or—as was the case with Kwame Nkrumah—economics, sociology, education and philosophy in the United States.

This once-before respect and cultivation of the pedigree of language and the, at once, direct and indirect route to language facility, especially for pro forma purposes, needs to be recovered. A healthy respect for language such that it may once again be employed in the construction, navigation and articulation of learning needs to be deployed. An attitudinal change Marshall Plan fashioned as an experiential marketing campaign is warranted and EGG Magazine and its sibling organization, UNIDPM, have a schema on offer which bespeaks Pinker’s observation.

“…imagine [a child] seeing through the rhythms [of language] to the structures underneath [i.e. linguistics]…” (Steven Pinker)

Pinker’s observation (displayed at this article’s beginning) and his call for imagination (as immediately above)—both of his book The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language—should serve as epiphanies for addressing the fractured lingual facility and the unhealthy disrespect for L1 instruction amongst many a Ghanaian.

UNIDPM, in addressing the above, has had as its programming rationale the following precepts: [1] have Ghanaians, more generally, process the issue of language instruction in order that they may eventually appreciate, if not also accept, the efficacy of L1 instruction for foundational learning; [2] more specifically, actively engage Ghanaian parents of early childhood education pupils in order to secure their investment in L1 practice, participation-and-all; and in the process one may prod them into becoming enlightened education consumers; [3] strategic-wise, have the governance of education service delivery employ a participatory dialogue approach between and amongst early childhood education stakeholders—going above and beyond a mere messaging and pedantic social marketing approach and onwards to an experiential marketing exercise in the process—so that understanding and support is engendered (i.e. from the bottom up) rather than serenaded (i.e. from the top, down). In effect, a peripatetic ‘conversation’ with ‘Missourian’ parents about the finer details of L1 instruction and the discerning features and functions of language will be achieved.

This innovative experiential marketing exercise staged as a focus group session and conducted in a local language has so far been conducted in four out of eleven ‘official’ Ghanaian languages. Peripatetic conversations in Ga, Fante, Akwapim Twi and Ewe undertook the following diagnostic and digestive pathway with parents/guardians of early primary education pupils:

- A pre-recording orientation (during equipment setup) which prompts parents…

- to gather their views and opinions on L1 instruction

- to reflect on their own earliest school days

- to compile their questions they have of government

- A context-setting, warm-up ‘small talk’ session which welcomes parents to walkabout…

- the utility of language for thought/thinking and expression/articulation

- the importance of ‘our’ oral tradition and its role in knowledge transmission and the sharing of culture and tradition

- the realization that language is the lifeblood of comprehension and understanding, whereby a simulated instructional exercise is conducted in a language uncommon to the participants

- A participatory diagnostic dialog addressing the connection between language and learning, most especially the highlighting of the following discernments:

- the role of language in learning, i.e. the use of language to effect learning, especially given the preceding exercise

- the nicety that L1 instruction is ultimately about the use of language to learn rather than, simply, being about the learning of a (local) language

- the highlighting of the personal experience of one of the participants who might have lived through the prior era of L1 instruction (e.g. a grandparent of a pupil)

- A participatory yet instructional dialog which digests the niceties about the academic interrelationships between linguistics and language as well as learning and assessment in the following ways:

- Delve into the deconstruction of linguistics and language with participants – for example the basic concept of phonics whereby a letter and a combination of them are expressed as sounds; and when formed as words they’d have meaning, and-so-forth-and-so-on.

- Digest the concept that language is, at once, the method for instruction, the medium for learning/comprehension and the tool for testing/assessment

- Orientate participants about Ghana’s L1 policy

- Allow for a coalescing and reflecting deliberation amongst participants that seeks to engender understanding, toleration and support for the concept as well as the practice of L1 instruction, never failing during the process to discern and discuss a parent’s role and responsibility in effectuating this policy, most especially the need to read to one’s child as well as participate in their homework or out-of-classroom learning.

—–0—–

The conduct of the above programming which was and has to be recorded should then be broadcast on radio stations across country. Ghanaians at large may then be able to listen in on a structured conversation about local language instruction and its utility to literacy education. District Education Officers, preferably in the persons of a District’s Local Language Coordinator and/or Public Relations Officers, ought to serve as co-hosts to a radio station’s emcee/host/disc jockey when these conversations are aired. This arrangement should help prevent the degeneration of a call-in segment of any one broadcast into an incendiary and mal-informed gabfest. Additionally, each broadcast should be transcribed so that it may be made available for future programming design in the areas of social marketing and advocacy campaigning as well as policy crafting and academic research.

Further programming could also include the following: [1] roundtable discussions with Parliamentarians that sit on the Select Committee on Education, [2] focus group sessions with sector functionaries and [3] talking-head opinion leaders who will make the rounds on Ghana’s media outlets.

—–0—–

By the above methods, the issue of L1 instruction and literacy education could permeate the mind of many a headstrong Ghanaian who derides local language instruction; who gawks at locally-acquired foreign accents and who only appreciates the cultural, but yet cosmetic, utility of local language, these among other lingual and linguistic crimes and misdemeanors.

“The jury is out”…

—–0—–

Postscript:

- Egg Mag will be recording a reflective videoscript and/or podcast with the four facilitators of the Fante, Ga, Ewe and Akwapim Twi sessions. Among other things, they will be recounting the dynamics of the sessions and recalling anecdotes that characterize the mindsets of participants. First-up, a conversation with the Fante facilitator and co-designer of the above experiential marketing process may be listened to on our podcast, both on iTunes and Sound Cloud.

Please stay tuned and check in for the ensuing others…

Follow us on social media: